The Small Business Balance Sheet

The income statement is an easier read and gets most of the attention. But the balance sheet has a lot to say about the setup and health of a small business.

The balance sheet is a snapshot of a company’s assets and sources of financing at a specific moment in time. The balance comes from the fundamental accounting equation which states that the dollar value of a company’s assets (what it owns) must equal the dollar value of its liabilities (the capital contributed by creditors) plus the dollar value of its equity (the capital contributed by shareholders/owners). On any given day, the company balance sheet tells its readers the amount and sources of capital that has been invested in the company and how that capital has been put to use.

The assets side of the balance sheet reflects the nature of the industry and the preferences of individual owners with respect to how they want to conduct business within that industry. The liabilities and equity side depends on owners’ choices on how to finance their assets, the choices being short-term and long-term debt or shares and retained earnings. The specific mix of debt (capital from creditors) and equity (capital from shareholders) employed in a company is referred to as its capital structure. It’s an important decision for small business owners to make. I’ll cover some of the factors involved a little later in this post.

The small business asset mix

Companies invest their capital in a mix of assets they’ll need to produce and provide their goods and services to their markets. For small businesses, the main asset categories tend to be cash, accounts receivable (AR), inventory, and property, plant, and equipment. The specific asset mix will depend on the industry.

For example, service businesses, like marketing agencies and accounting firms, are unlikely to have inventory. But they’re probably going to have to extend credit to their customers which means they’ll need to fund accounts receivable. Meanwhile, retailers are going to carry inventory, the products they’ll sell to their customers, but, because their customers also pay when the sale takes place, they’re not going to have to worry about AR.

It’s an inexact science though. Hair salons are service businesses that also sell products to their clientele. Flower shops are retail businesses that may also provide home décor classes to their customers. Accounting firms are service businesses that need relatively little equipment to provide their services. Tire and automotive shops are retail and service businesses that need specialized equipment and supplies, a higher investment in facilities, and the capital to fund AR if they’re going to serve commercial customers.

These capital allocation decisions are only partially determined by the industry that a business is in. Small business owners can choose to strategically invest more or less in each asset category as a means to securing a competitive edge. Some restaurants, for example, can invest heavily in renovations, furnishings, equipment, and inventory as a means to position themselves as offering a fine dining experience. Others, when capital is scarce, can strip everything else down and focus on simple, delicious food.

Asset levels typically determine the capacity of a business to generate sales. Some businesses can be more efficient than others and produce higher sales from each dollar of their assets. But, generally, for a company considered in isolation, sales growth requires asset growth: more cash, more inventory, more equipment, more stores, etc. So a growing company will have a growing asset base, which will require more capital on the other side of the balance sheet.

Creditors vs. Shareholders

Creditors and shareholders, the two groups of capital providers, both seek returns on their investments, but they have different appetites for risk and, therefore, different expectations for return.

Creditors prefer lower risk. They can live with a lower return if they can be shielded in some way from the downside of losing their investment. Thus, they provide capital in exchange for a fixed, legal claim on a company’s assets if the company fails to make its required payments or adhere to debt covenants. A company must make interest payments on borrowed funds and eventually repay the borrowed amounts as per the agreed upon terms and timing. Failing to do so or failing to comply with other restrictions put in place as part of the loan agreement runs the risk that creditors will force the company into bankruptcy in order to recover their invested capital.

Shareholders are equity investors. They provide capital in exchange for an ownership stake in a company rather than a fixed claim on its cash flows. They’re willing to share the inherent risk in business in exchange for a share of the rewards. Which also means they pay for their share of business failure. On the balance sheet, shareholders’ equity is the difference between assets and liabilities; it represents a residual interest in a company’s assets. In the event of a bankruptcy, shareholders get what’s left of the assets once creditors’ claims are covered. If there’s nothing left, the shareholders get nothing. Their investment is wiped out.

If, however, a company grows and prospers, the shareholders get the upside. They are entitled to their proportional share of the company’s profits, which, rather than being limited to a fixed amount as in the case of creditors, can eventually and substantially exceed the amount of their original investment. In profitable years, shareholders can be paid out through dividends. Or they can see their equity in the company increase if management decides to retain earnings in order to fuel further growth.

Debt vs. Equity

Given they have access to both options, why would small business owners prefer debt to equity? Debt seems to be the harsher, riskier option when it comes to financing. Owners have to repay debt. They’ll end up in court if they fail to do so. But there’s no need to repay equity investors if things go south in a business. Short of hard feelings and possibly a sense of guilt, owners can just walk away. On the whole, equity seems cheaper than debt. But small business owners often see it differently.

In order to raise money through equity, you have to give up equity. And small business owners are generally reluctant to give up equity. They’re usually optimists and they believe in their business’s upside: it’s going to be successful, it’s going to grow, it’s going to generate profits. They want to keep as much of that upside for themselves as they can for as long as they can. That’s how to win.

Felix Dennis, an entrepreneur who ranked at one point in the top 100 of Britain’s wealthiest individuals, captures this perspective in his book, How to get Rich:

Nothing counts but what you own in the race to get rich. If you haven’t much skill, or much wit, or much talent, or much luck, and yet you insist on owning more than your fair share of any start-up or acquisition, then you can become rich. If you take what you’re given, you will probably not get rich.

(To drive home the point, the above quote appears in a chapter titled Ownership! Ownership! Ownership!)

What’s more, small business entrepreneurs also want control; they want to run their business without investors or financial partners nervously looking over their shoulders and offering advice. Taking on debt allows that, even if it entails greater business risk and a different set of scrutinizing eyes to worry about. Creditors, though they may be strict in requiring companies to maintain financial benchmarks, generally have no interest in backseat driving their portfolio businesses, at least when alarms aren’t going off.

Finally, the use of debt plays to the concept of leverage, which in finance not only allows companies to “control assets they couldn’t control otherwise” as Mihir Desai explains in his book, How Finance Works, it also allows the owners of those companies to increase their returns on the money they have invested. This is analogous to using a mortgage to purchase a home. The homeowners get a larger home than their present financial resources would allow. And, if the value of their home increases, they get a better return on the money they have invested than they would have received if they had purchased the home outright.

There is a limit to the amount of debt that the shareholders and creditors of a business can tolerate, however. Because debt incurs interest, and interest has to be paid out of revenue, debt is a drag on the overall profitability of a business. Lower profits also restrict the ability of the business to deal with unexpected challenges, self-fund its growth, and to accumulate the resources needed to eventually repay its debt. Missing interest or principal payments is a dangerous line to cross. Debt adds a lot of pressure to the already pressure-filled reality of running a small business. That’s why the debt-to-equity ratio and its variants are closely watched measures of a small business’s health and its ability to meet its financial obligations.

A case study

To recap, a balance sheet is a snapshot, a statement of a company’s financial position at a specific moment in time. A single balance sheet offers insight into a company’s asset mix and its capital structure (debt vs. equity), but only on a specific date. To see how a company’s asset mix and capital structure changes as the company evolves and experiences periods of success and struggle, we’ll need to see snapshots taken at different moments in time.

Let’s try then to develop a better understanding of how to read and interpret the balance sheet by following one fictional small business, incorporated in 2017, called Eight Leaves. Eight Leaves is a small retail shop located in a strip mall in an affluent suburban neighborhood in Anywhere, Canada. It was started by two close friends, Tina and Yasmin, both career marketing professionals in their late-20s.

Tina and Yasmin have spent their academic and working lives in the business world, and they’ve always talked about going into business for themselves. They’ve designed and run successful advertising campaigns for local and regional businesses. (Not all of the campaigns have been successful, if we’re being honest; but enough to give the two friends confidence that they can make things happen.) They’ve followed successful entrepreneurs on social media and observed how they’ve launched and built their brands. They’ve talked over ideas, conducted market research, and, over the past two years, arrived at a couple of retail ideas that they told each other they would pursue if the right opportunity came along.

So when they noticed the “Store Closing” sign go up in the window of a small fashion retailer four shops down from their regular Starbucks, they decided it was now or never. With help and encouragement from friends, family, and husbands, they settled on the idea of a flower and home décor shop, drew up a business plan, incorporated their business, put in a chunk of their savings, raised more money from friends, family, and husbands, and got ready to negotiate a lease with the strip mall owners.

A condensed balance sheet

Let’s take a look at the company’s balance sheet on the eve of this negotiation. I’m going to skip the details and keep the presentation at a high level throughout the post. It’ll help focus our attention on what we’ve discussed so far: the asset mix and the capital structure of the company, that is, what the company owns and how the assets were funded.

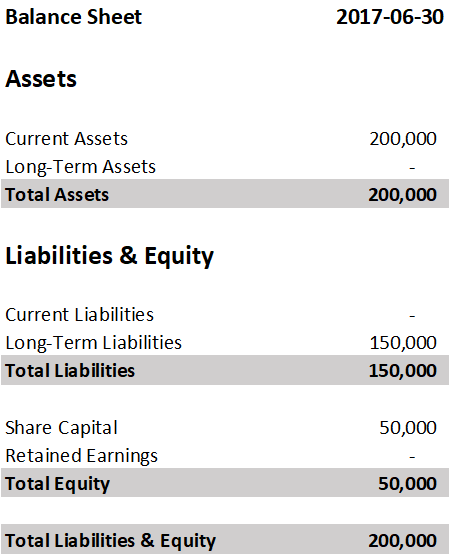

Here we see the traditional accounting breakdown of assets and liabilities into current and long-term categories. The dividing line between what’s considered current and what’s considered long-term is usually one fiscal year or operating cycle.

To keep things simple, a business’s current assets include cash and anything that’s expected to become cash soon (like inventory and accounts receivable), soon being no later than a year. Its long-term assets include equipment, vehicles, and leasehold improvements: anything that helps the business generate revenue but gets depleted or used up over the years.

A business’s current liabilities include any obligations (like accounts payable, notes payable, the current portion of long-term debt) that the business has to settle with cash soon, soon being no later than a year. Its long-term liabilities include loans that need to be repaid some time after the current year.

The two line items under equity reflect the different ways in which shareholders can invest in a business. First, they can invest by purchasing shares offered directly by the company. These amounts are recorded under share capital. Second, entrepreneurs (or management) can decide to retain some or all of their company’s profits to fuel future growth, instead of distributing them to shareholders via dividends. These amounts are recorded under retained earnings.

Through retained earnings, shareholders are effectively reinvesting their share of the company’s profits in the business. The retained earnings line keeps track of how much wealth shareholders have accumulated in the business, and how willing they’ve been to fund the growth of the business with their own money. If an entrepreneur chooses to increase retained earnings while keeping debt steady (or even paying it down), she’s expressing a preference on capital structure, that is, a preference for equity (self-generated funds) over debt (external funds) to fund her business. The nice (and not unexpected) benefit of this choice is that a self-funded business with a healthy amount of retained earnings becomes attractive to lenders as well, at least according to the BDC.

Banks will generally lend about three or four times what the company has in terms of equity, a major component of which is retained earnings.

The initial asset mix and capital structure

Let’s quickly go over the specifics for the company’s first balance sheet, dated June 30, 2017. At this moment in time, the share capital ($50K) represents the money invested by the two shareholders, Tina and Yasmin. Through their share purchase, they’ve each put $25K of equity into the company.

This is an unusual choice. Most entrepreneurs choose to assign a nominal value to their shares and share capital. They make the entirety of their capital contribution through shareholder loans. They would only show an entry under share capital if they took money from investors which isn’t the case here. And, because lenders want to see how much money owners have committed to their business, they’ll typically move shareholder loan amounts into equity when calculating debt-equity ratios. So, to my knowledge, the share capital move doesn’t help them in obtaining bank financing.

I’m showing part of their financial commitment as equity and part as debt to give equity an initial non-zero balance. It makes it simpler for me to reason through, i.e., Tina and Yasmin’s plan is that, when the company can afford to do so, they’ll get paid back their $50K shareholder loan, but they’re going to leave the other $50K in the company and treat it as any other investment that they want to see grow.

The $150K in long-term debt breaks down as follows. Friends and family loaned the new entrepreneurs $50K, their husbands loaned them $50K, and Tina and Yasmin took out personal lines of credit to cover the remaining $50K. The friends decided to finance mostly through debt because they were confident that they could manage the responsibility and they didn’t want to take on passive investors. The interest rate on the debt was very reasonable given that this was their first go at entrepreneurship and the risky nature of entrepreneurship in general. (That’s what friends, family, and husbands are for.) Tina and Yasmin decided to personally loan the business the extra $50K (rather than add to their equity) because they expect to pay this money back to themselves (as well as paying back their other creditors) within their first three years of running the store.

All of the money they’ve raised was recorded as cash on the asset side of the balance sheet. As of the balance sheet date, it’s sitting in the company’s bank account, waiting to be put to work.

The night before Opening Day

After three and a half months of long days spent dealing with contractors and suppliers, the store is finally ready to open. The friends left their jobs in late summer to devote their full attention to their new venture.* They managed to get concessions from the landlord on rent for the first year (which helps cash flow). And they’ve hired a couple of part-time employees (which hurts cash flow). They’ve sourced a number of suppliers and placed and received a few orders to stock their shelves. There have been other launch related expenses; nothing extravagant, but still a drain on the company’s cash. So they’re anxious to open their doors and start generating sales.

* (I’m being a little reckless here with my characters’ choices. My business partner Darren’s view is that the friends shouldn’t quit their day jobs until the store is up and running solidly — and that they should hire no one until their husbands threaten to leave them. He considers these moves to be critical. I’m not sure how to achieve both objectives at once, but I know where he’s coming from. The money goes fast. There’s never enough money.)

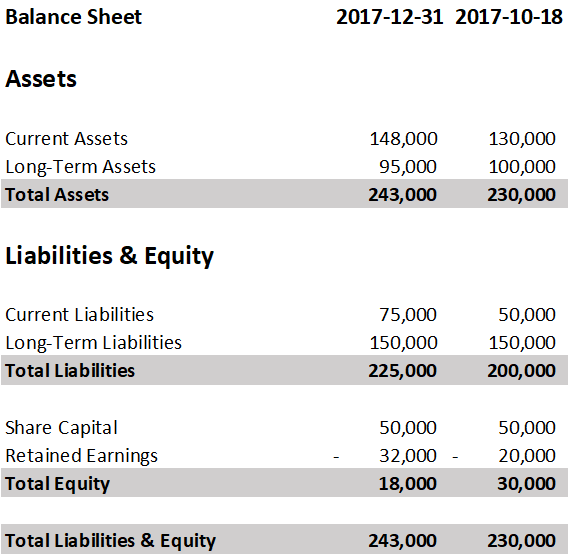

Let’s take a look at the company balance sheet on the night before opening day:

The company started with $200K in cash. $100K was spent on renovating and equipping the store. $20K was spent so far on rent, employees, interest, and launch related expenses. This reduced the cash asset to $80K. The company also acquired $50K in inventory which will have to be paid for in 30 days. The cash and inventory combined account for $130K in current assets. The $100K in long-term assets includes, as mentioned, leasehold improvements and equipment. The overall result is that the company has not only shifted its asset mix, it’s also increased its asset base.

This was made possible by using suppliers as an additional source of (short-term) capital. The $50K in current liabilities represents the amount owed in accounts payable (AP) for the initial orders. The 30-day payment window gives our young entrepreneurs a valuable source of working capital, which they’ll have to carefully manage if they want to succeed.

Finally, the retained earnings account has a -$20K balance. This is because the company has incurred $20K in expenses but has yet to generate sales. The retained earning reflect this loss. Tina and Yasmin are a little nervous about their cash situation, and their debt-to-equity ratio seems quite high, but they also know the game hasn’t really started yet. They’ve done a great job curating items for the store and getting the word out. They’re expecting a busy day and lots of sales when they open their doors in the morning.

The first year end

The first couple of months were, thankfully, a success. The store exceeded its modest sales targets. Tina manages the online marketing and advertising. She posts beautiful floral arrangements and home décor tips daily for their small but growing audience on social media. She’s reached out to local influencers and wedding planners sending them custom arrangements and small swag bags. Some have already responded and expressed interest in working together. Yasmin has been busy with buying and merchandising, sourcing new products, and managing their supplier relationships. Despite hiring a third part-time employee, they’ve both been spending more time in the store. The holiday season has been hectic but fun.

Early in 2018, they get their paperwork together for their CPA so she can prepare and file their corporate tax return. Tina’s husband has been helping with the bookkeeping so they’ve stayed current with their sales and payroll taxes. It’s busy season in the accounting world so it takes a few weeks for the CPA to get everything ready. The partners think they’ve done well because their sales numbers have been good. But cash keeps decreasing which makes them wonder.

Here’s what the balance sheet looks like at the end of 2017:

Eight Leaves ended the year with a $32K loss. Despite sales exceeding targets, gross margin was quite a bit lower than what Tina and Yasmin expected. Yes, they ran an opening week sale and a sale for the holidays, but they’re not sure why two weeks worth of promotions would have dented their margins over the entire two month period. Their operating expenses came in high as well, with wages and advertising being the main culprits. This was also concerning. They knew from their professional experience that customers don’t just show up; companies have to advertise. They both worked through their marketing strategy and felt it was solid, but maybe it wasn’t producing the results they needed relative to the financial resources they were committing to it.

Tina and Yasmin were both taking a small salary, less than half what they were making in their marketing jobs (at a meager hourly rate too, considering the amount of time they were putting into the business). They did start paying themselves from the company as soon as they quit their jobs however, and this was before the store opened. It crosses their minds that their sales level (which has slowed down in January) can’t support their current payroll. By the time they see the numbers, they’ve already cut back to two part-time employees. They wonder if it maybe makes sense to cut some more, starting with their own wages.

Current assets have grown to $148K. Unfortunately, cash has dropped to $40K and inventory has grown to $108K. Yasmin took advantage of volume pricing on some unique items she felt they’d be sure to sell. They’re doing fine moving their floral inventory but the shelves are still full, even after the holiday rush. They agree to slow down on their ordering while they work at converting more of their existing inventory to cash. The long-term assets category was lower after the CPA applied depreciation to their leasehold improvements and equipment.

Overall, the results weren’t great. But Tina and Yasmin, while disappointed, aren’t discouraged. Financial discipline is a little new for them and the learning curve is steep, but they’re fast learners. They can see what needs to get fixed in their financials and they’re already taking steps. Rent is going to go up later in 2018 so it’ll be a challenge getting the company to profitability for the year. But they’re confident that if they can create the right retail experience, they’ll be able to build some real momentum for their brand. It’s just a matter of experimenting while being more prudent with their financial resources.

The year before Covid

Two years have flown past and Tina and Yasmin feel like they’re really on the right path. The store is consistently generating profits, they’re taking home reasonable salaries, sales keep going up, and they have a healthy balance in the bank account, which gives them some much appreciated breathing room. With two years of solid operating results under their belt, they’re ready to approach their bank for either an operating line of credit or a business loan. They plan to expand into online sales and the corporate gift market in 2020. They’ll need additional resources for that.

Plus, they want to pay back the remaining debt from their startup days. It was awkward at times dealing with personal relationships and money. Nothing dramatic, but, now that they’ve paid back friends and family, it’s been better for everyone to go back to just being friends and family again. All that’s left now on the company books is the $100K owed to Tina and Yasmin and their husbands. It would be nice for the two couples to get their money back, even partially, but they don’t want to put extra pressure on the business. That’s also why they’re counting on the bank loan this year.

Let’s take a quick look at the pre-Covid balance sheet:

Assets have grown to $358K. Under current assets, the business now has $198K in cash and $100K in inventory. The entrepreneurs could take the excess cash out as dividends, but they’ve decided to leave the money in the business, both for peace of mind and in preparation for their loan application. They’ve maintained inventory levels near where they first started even though sales are now approaching $1M, a much bigger number than what they pulled in their first few months. They’re better at reading what sells and what doesn’t (or they’ve become much better at selling what they’ve stocked… or both). And they’re careful to weigh cash flow impacts when making their buying decisions. The long-term assets category continues to decrease via depreciation applied to the equipment and leasehold improvements. The CPA reminds them that depreciation is a non-cash expense that doesn’t affect their cash flow. Yasmin reminds Tina they still haven’t learned to speak accounting.

AP has stayed about the same from two years ago. Suppliers are willing to offer better terms and incentives now that Eight Leaves has a track record. This will certainly help with cash flow when the company expands into the corporate gift market in 2020. To support the expansion, they’ll need to grow their inventory and source new product categories. Long-term liabilities have come down because they’ve managed to repay their friends and family from their after tax earnings.

Equity has gone up as the entrepreneurs have left the last two year’s earnings in the company. The debt-to-equity ratio is almost 1:1 now. For a young company, the balance sheet is healthy. Tina and Yasmin are excited about 2020. They’ve been hearing news reports about a virus, but they’re both too busy with the store and their future plans to pay too much attention.

Everybody has plans

Covid turned the world upside down. Non-essential businesses were required to close. Sales went to zero. With ever-changing restrictions and rules, our partners, like every other stressed out small business owner, didn’t know what would happen next. Plans went out the window. They couldn’t rely on their storefront, at least not for the near future. They had to get their business online and fast. With the help of a tech-savvy friend who wanted to learn Shopify, they managed to do just that. Their online store launched in a little over a month. Along the way, and with some help from their CPA, they navigated a thicket of government programs and eligibility rules. With their books up to date, they were relieved to find they qualified for wage and (later) rent supports.

But the store was still closed. And with the company burning cash while still paying rent, key suppliers, and their employees (though they knew they would be getting wage subsidies, the timing still made them nervous), the first part of 2020 was scary. It helped that the partners had built up a financial cushion. It also helped that they had built a loyal following in their community. When they opened their online store, orders immediately flooded in. It turned out everyone was stuck at home and looking to improve their living spaces. (What’s better for that than a stream of dazzling flower arrangements and uniquely designed home décor?) And the government was flooding the economy with cash. It was still hard work. Tina and Yasmin took a real-time crash course on running an online business during a global pandemic. They made plenty of mistakes, some more costly than others. But they kept at it until they found their feet, and, quite unexpectedly from the way 2020 started, by year’s end, their sales were the highest on record by a fair stretch.

Here’s how things look in the company’s 2020 balance sheet:

At year’s end, the company was carrying $150K in inventory and a very healthy $290K in cash. With retained earnings almost doubling for the year, its assets were now primarily funded by shareholder equity. Their long-term liabilities grew because they took advantage of the CEBA loan, not wanting to deal with the uncertainty and time commitment of pursuing a bank loan. Overall, they were in a very good position with their three-year-old business. Their physical store was open (and closed) and open (and closed) and open… but their online sales kept growing and growing.

In short, by the end of 2020, our two friends had a profitable, growing business, with good cash flow, a good return on their investment, and a very manageable level of debt. They were getting paid reasonably well for their roles in the business. Their husbands were (still) very supportive. So they were confident enough in how things were going and how they were getting along together that they continued to reinvest their profits to grow the business even more.

Wrapping up

A company’s balance sheet shows its mix of assets and the source of capital for those assets on a specific date. In my experience with our company Origami (which provides bookkeeping and year end services to Canadian small businesses) small businesses typically start with a relatively small amount of capital contributed by the owners and members of their network. The fictional company I used in this post followed this template. Their start wasn’t typical of what we see (it often takes longer than the first couple of years to start generating profits that can be used to grow), but I wanted to focus here on the changes in a balance sheet you should expect as your business starts to produce strong financial results.

Over their first 3 and some years of operation, our two friends, Tina and Yasmin, started with a balance sheet that was heavily leveraged and ended with a balance sheet that showed more equity than debt, with most of the turnaround due to generating profits and retaining those profits in the company. As their business grew, so did their assets. Their asset mix shifted more to current assets than long-term assets; they accumulated cash and depreciation reduced the book value of their fixtures, equipment, and leasehold improvements. They were largely able to fund the asset growth through internal funds. And they were also able to pay down some of the debt that they needed to launch their business. Heading into 2021 with confidence in their concept and in their execution, they planned for a second store in a year or two. They expected to fund that expansion mostly from internal funds.

Let’s end on that happy note.